Is the ozone layer a risk?

The overall picture is clear: The Montreal Protocol reduced use of ozone-depleting chemicals and will lead to the healing of the ozone layer. This is an important goal because stratospheric ozone protects us from exposure to ultraviolet radiation, which can increase the risk of cataracts, skin cancer and other detrimental effects.

The overall picture is clear: The Montreal Protocol reduced use of ozone-depleting chemicals and will lead to the healing of the ozone layer. This is an important goal because stratospheric ozone protects us from exposure to ultraviolet radiation, which can increase the risk of cataracts, skin cancer and other detrimental effects.

Of course, this forecast would be wrong if nations deviate from their treaty commitments, or if the scientific community fails to detect possible emissions of gases that could deplete the ozone layer but are not covered by the treaty.

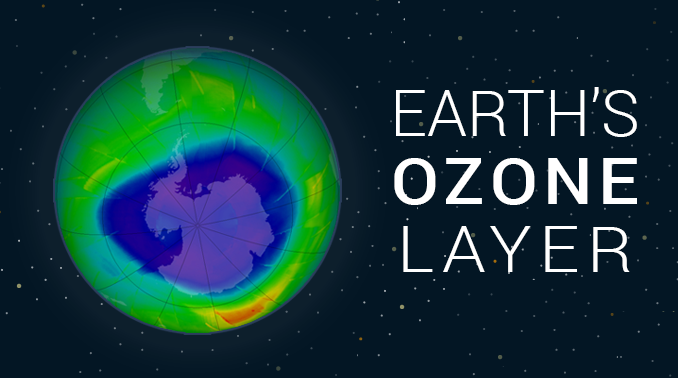

Our understanding of stratospheric ozone depletion has grown steadily since the mid-1970s, when Mario Molina and F. Sherwood Rowland first suggested that the ozone layer could be depleted by chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs – research that earned a Nobel Prize. In 1985, Joseph Farman reported on the formation of an “ozone hole” – actually, a large-scale thinning of the ozone layer – that develops over Antarctica every austral spring.

Further work by Susan Solomon and colleagues clearly attributed the ozone hole to CFCs and other ozone-depleting chemicals that contained the elements chlorine and bromine. They also highlighted unusual reactions that take place on polar stratospheric clouds.

It takes decades to cleanse CFCs and other ozone depleting substances from the atmosphere, so even after the Montreal Protocol went into effect, their concentrations did not peak until around 1998 and are still high. Nonetheless, based on atmospheric observations, laboratory studies of chemical reactions and numerical models of the stratosphere, there is a general consensus among scientists that the ozone layer is on track to recover around 2060, give or take a decade. We also know that the future of the ozone layer is intricately intertwined with climate change and our irresponsibility.

By Sofía Moreno Royet, Step 8.